In most parts of the world, dreams are deeply personal — fleeting stories that vanish with the morning light. But in Korea, some dreams are considered so valuable that people literally buy and sell them. This centuries-old custom, known as kkum panmae (꿈 판매) or dream trading, remains one of the most fascinating and unique aspects of Korean dream culture.

So what exactly does it mean to sell a dream? Why would someone pay for something as intangible as a dream? And how did this unusual practice survive into modern times? Let’s explore the intriguing world of Korean dream trading — a blend of superstition, symbolism, and the belief that luck can be shared.

Table of Contents

- The Origins of Dream Trading in Korea

- How Dream Trading Works

- The Most Popular Dream to Buy: The Pig Dream

- Other Lucky Dreams That Are Often Sold

- Modern-Day Dream Trading

- Dream Trading Around Special Occasions

- The Psychological View: A Way to Share Hope

- What Dream Trading Reveals About Korean Culture

- Final Thoughts: The Beauty of Sharing Dreams

The Origins of Dream Trading in Korea

Dream trading has roots that stretch back centuries, originating from Korean shamanistic and folk beliefs about dreams as divine messages. In traditional Korean culture, dreams — especially vivid or symbolic ones — were thought to be omens that could predict the future.

A “good dream” (ggot kkum — literally “flower dream”) might foretell wealth, success, or pregnancy, while a “bad dream” could warn of danger or misfortune. Because dreams were seen as spiritual gifts, a person who had a particularly auspicious one could “transfer” its luck to someone else — usually by selling or gifting it.

At its core, dream trading is not about the dream itself, but about transferring the good fortune associated with it.

How Dream Trading Works

The practice usually starts when someone experiences a powerful or symbolic dream — one that seems especially lucky. Classic “good dreams” in Korean culture often involve things like:

- Pigs (symbols of wealth and prosperity)

- Dragons (signs of power, status, or success)

- Snakes (linked to money or upcoming opportunities)

- Fruit trees or flowers (indicating fertility or growth)

- Tigers (protection and strength)

If the dreamer doesn’t want or need the fortune implied by the dream — or if someone else feels the dream fits their current life situation — they might “sell” it.

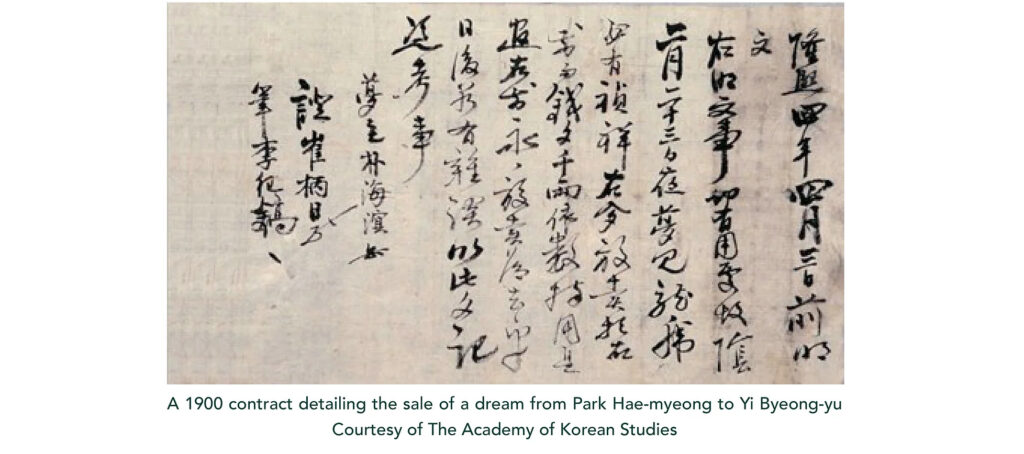

The “sale” can be as simple as verbally declaring that the dream now belongs to someone else, often with a symbolic exchange of money. Sometimes people write down the dream details and sign their names, treating it almost like a spiritual contract. The key is intention — the belief that luck can be passed on through mutual agreement.

For example, if a person dreams of a pig, they might sell the dream to a friend who recently started a business, believing it will bring them prosperity.

The Most Popular Dream to Buy: The Pig Dream

No dream is more famous in Korea than the pig dream (dwaeji kkum). In Korean culture, pigs have long symbolised wealth and abundance, partly because of their round, full shape and historical association with prosperity.

If someone dreams of a pig — especially one that’s large, pink, and healthy — it’s considered an incredibly lucky omen. These dreams are so prized that people often rush to “buy” them before the luck fades.

In many cases, the dreamer might jokingly say, “I’ll sell you my pig dream for ₩10,000,” and the buyer agrees, transferring the “fortune” symbolically through the money. Even though everyone knows it’s not literal, it’s taken seriously enough that the buyer might feel genuinely more confident or hopeful afterward.

In modern times, pig dreams are still traded — sometimes mentioned on social media or online communities, especially around major life changes like exams, weddings, or business launches.

Other Lucky Dreams That Are Often Sold

While pig dreams are the most popular, Koreans also trade other types of lucky dreams, each with their own meanings:

- Dragon dreams – Symbolise fame, power, and career success. Often bought by entrepreneurs or those seeking promotion.

- Snake dreams – Represent money or opportunities, especially if the snake doesn’t attack but simply appears.

- Flower dreams – Seen as signs of romance or creative growth.

- Baby dreams (taemong) – Dreams predicting pregnancy or the birth of a special child. Sometimes, if someone who isn’t planning to have a baby dreams of one, they may “sell” the dream to a friend who’s trying to conceive.

Each of these dream types ties into deep-rooted Korean beliefs about luck being transferable — almost like a form of spiritual energy that can change hands.

Modern-Day Dream Trading

You might think that dream trading sounds like a relic from the past, but it’s surprisingly alive and well in modern Korea.

Even today, people mention selling or buying dreams in casual conversation or on social media. The transactions are usually small — symbolic exchanges meant more for fun than profit — but they carry emotional weight.

For example:

“I dreamed of a golden pig last night. My friend’s about to start her new job, so I sold it to her for good luck.”

It’s a playful yet sincere gesture, reflecting how Koreans blend superstition with social connection. Many see it as a way of sharing positive energy and supporting loved ones.

Some younger Koreans, especially those who grew up hearing these beliefs from grandparents, treat dream trading as a cultural charm — part tradition, part fun, part spiritual insurance.

Dream Trading Around Special Occasions

Dream trading often peaks around Lunar New Year (Seollal) or Chuseok (Harvest Festival) — times when people reflect on fortune and the future. Dreams seen around these festivals are believed to carry stronger spiritual messages, and selling a good one can bring both parties luck for the coming year.

Business owners might also pay special attention to dreams during major deals or openings. A lucky dream before a big project can feel like a divine “green light,” while a bad dream might prompt ritual cleansing or symbolic reversal actions.

The Psychological View: A Way to Share Hope

While the tradition is rooted in superstition, psychologists interpret dream trading as a positive social and emotional coping mechanism.

Dreams often reveal our hopes, fears, and subconscious desires. By selling or buying them, people create a shared narrative of optimism — turning an abstract dream into a tangible source of motivation. It’s less about whether luck actually transfers, and more about believing in possibility.

In a society that values harmony and emotional connection, dream trading functions like a social ritual of encouragement — a way of saying, “I want you to succeed, so I’ll give you my good dream.”

What Dream Trading Reveals About Korean Culture

The dream trading tradition offers a glimpse into Korea’s deep spiritual heritage, where dreams bridge the human and divine. It reflects:

- Respect for dreams as sacred messages

- Belief in collective fortune and shared destiny

- The blending of superstition and social connection

- A practical optimism — the idea that good luck can be cultivated

While most people today approach it playfully, the underlying idea remains profound: dreams hold meaning, and sharing them can shape our emotional reality.

Final Thoughts: The Beauty of Sharing Dreams

In a world where everything is digital and fleeting, the Korean tradition of buying and selling dreams feels refreshingly human. It’s not about money or superstition alone — it’s about believing in something unseen, about giving and receiving hope.

When someone “sells” a dream, they’re really passing on a bit of optimism — the belief that good fortune can be shared, and that one person’s luck can light the way for another.

So the next time you wake up from a dream that feels golden — whether it’s filled with pigs, dragons, or simply a sense of peace — remember this: somewhere in Korea, that dream could be worth more than gold.

Disclaimer: Dream interpretations on DecodeYourDream.com are for informational and cultural purposes only. Meanings may vary depending on personal beliefs, emotions, and context. Always interpret dreams through your own life experiences.

One Comment