In South Korea, dreams are not brushed off as random images from a sleeping mind—especially when an important exam is approaching. For generations, Koreans have believed that certain dreams carry omens of success, luck, and future outcomes. Among students, parents, and even teachers, the idea of having a “good dream” before an exam is taken seriously enough to influence emotions, confidence, and sometimes even behaviour the next day.

This tradition is deeply woven into Korean culture, combining folklore, symbolism, Confucian values, and modern academic pressure. To outsiders, it may sound like superstition. To Koreans, it is a psychological ritual—one that offers comfort, hope, and reassurance during moments of extreme stress.

So what exactly are good dreams in Korean exam culture, where did this belief come from, and why does it still matter today?

Why Exams Carry Such Emotional Weight in Korea

To understand the importance of dreams before exams in Korea, it helps to understand how central exams are to Korean society.

High-stakes exams—especially the College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT), known as Suneung—are seen as life-defining moments. These exams influence not only university admission, but future job prospects, social status, and even marriage expectations.

With so much pressure attached, emotional reassurance becomes essential. Dreams serve as a symbolic space where anxiety, hope, and anticipation are processed. A good dream becomes more than a pleasant experience—it becomes a psychological anchor.

What Is a “Good Dream” (길몽, Gil-mong) in Korean Culture?

In Korean tradition, dreams are broadly divided into:

- 길몽 (Gil-mong) – auspicious or lucky dreams

- 흉몽 (Hyung-mong) – ominous or unlucky dreams

Before exams, people hope for gil-mong—dreams believed to predict success, fortune, or positive outcomes.

Unlike Western dream interpretation, which often focuses on emotions and subconscious symbolism, Korean dream culture places strong emphasis on outcome-based meaning. A dream is not just about how it feels, but what it foretells.

Common “Good Dreams” Before Exams and Their Meanings

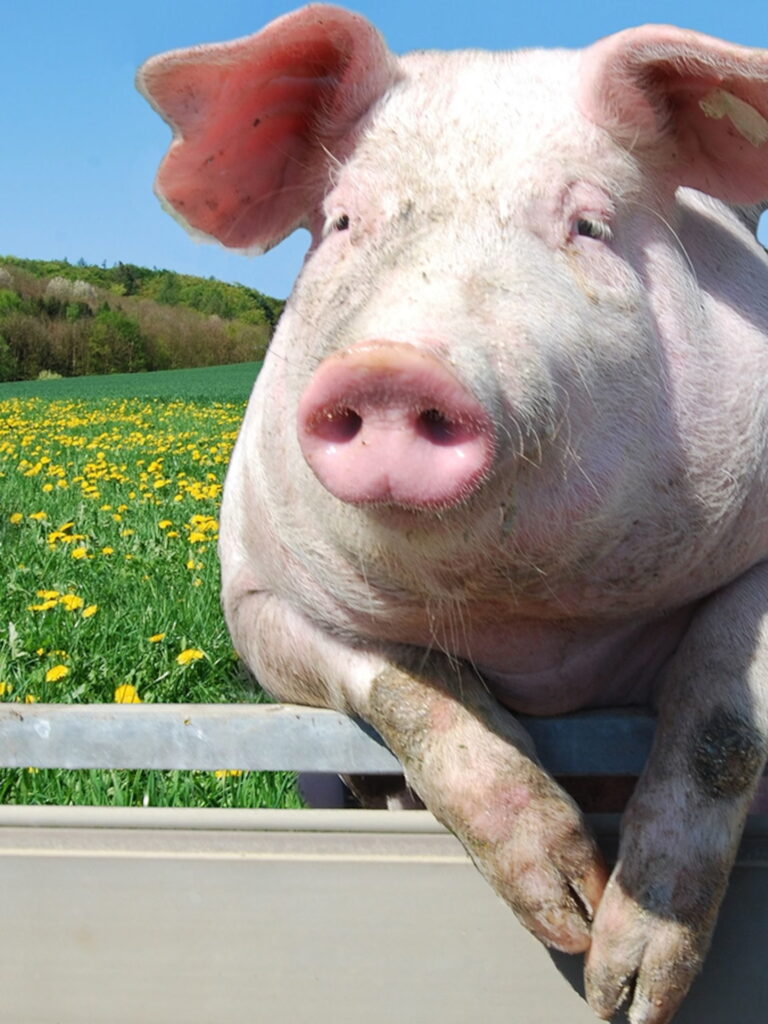

1. Dreaming of Pigs

Perhaps the most famous good dream in Korea, pig dreams are associated with wealth, luck, and success.

In exam contexts, dreaming of pigs is believed to indicate:

- Unexpected good results

- Financial prosperity tied to future success

- Favorable outcomes beyond expectations

Even today, students who dream of pigs before exams are often congratulated rather than comforted.

2. Dreaming of Gold or Treasure

Dreams involving gold bars, jewelry, coins, or buried treasure are considered powerful gil-mong.

Symbolically, gold represents:

- Achievement

- Recognition

- Rewards earned after effort

For students, this dream reinforces the belief that hard work will pay off.

3. Dreaming of Passing Through Gates or Doors

Gates, doors, and entrances carry strong symbolic meaning in Korean culture. Dreaming of entering a large gate or opening a door easily is interpreted as passing an important threshold.

Before exams, this is seen as a sign of:

- Successfully entering a desired school

- Overcoming barriers

- Smooth progression to the next stage of life

4. Dreaming of Clear Water or Swimming

Water dreams can be complex, but clear, calm water is considered especially auspicious.

Swimming comfortably or crossing a river safely symbolises:

- Emotional clarity

- Mental readiness

- Smooth passage through challenges

This dream reassures students that they are mentally prepared, even if they feel anxious while awake.

5. Dreaming of Dragons or Tigers

In Korean folklore, dragons and tigers represent power, intelligence, and protection.

Dreams involving these animals are believed to suggest:

- Exceptional performance

- Recognition from authority figures

- Rising above competition

These dreams are particularly prized before major national exams.

Dreams Parents Hope Their Children Will Have

Interestingly, the belief in good dreams is not limited to students. Parents often anxiously ask their children, “What did you dream about?” on the morning of an exam.

This question is less about curiosity and more about emotional reassurance. A positive dream calms not just the student, but the entire household.

Some parents even interpret their own dreams as signs for their children’s success, reinforcing the collective nature of academic pressure in Korean families.

The Practice of “Dream Trading” (꿈을 산다)

One uniquely Korean tradition related to dreams is “dream trading”—the idea that a good dream can be symbolically sold or shared.

If someone dreams of pigs or gold, others may jokingly (or seriously) ask:

“Can I buy your dream?”

While lighthearted, this reflects a deeper belief that luck can be transferred through acknowledgment and intention. For exam takers, hearing that someone dreamed well for them can provide a surprising boost of confidence.

Psychological Comfort vs. Superstition

From a psychological perspective, good-dream beliefs function as coping mechanisms.

Before exams, students often feel:

- A lack of control

- Fear of failure

- Mental exhaustion

A good dream restores a sense of balance. It gives the mind something positive to hold onto, reducing anxiety and reinforcing self-belief.

Even students who claim not to believe in dream symbolism often admit:

“It still feels better if the dream is good.”

This emotional effect is powerful—and measurable.

What If You Have a “Bad Dream” Before an Exam?

In Korean culture, a bad dream does not automatically mean failure. There are traditional ways to neutralise its impact.

Some people:

- Tell the dream out loud to “release” it

- Wash their face or hands in the morning to symbolically cleanse bad luck

- Reframe the dream as symbolic stress rather than a prediction

In fact, some interpretations suggest that bad dreams release negative energy, allowing waking life to proceed more smoothly.

The Role of Confucianism and Effort

A key reason this dream tradition persists is because it does not replace effort.

In Confucian-influenced Korean culture, hard work, discipline, and preparation remain paramount. Good dreams are seen as supportive signs, not substitutes for study.

A good dream does not mean you can skip revision. Instead, it reassures you that your effort aligns with a positive outcome.

Dreams in Modern Korean Exam Culture

Despite technological advancement and global education standards, dream beliefs remain surprisingly resilient in modern Korea.

Students today may:

- Laugh about dream meanings online

- Share dream stories on social media

- Look up dream interpretations late at night

Yet the emotional impact remains the same. A good dream still brings relief. A bad dream still causes unease.

In a system where academic pressure remains intense, dreams offer a rare space where the subconscious can speak without judgment.

What This Tradition Teaches Us About Dreams

The Korean belief in good dreams before exams highlights something universal: dreams matter most when we feel vulnerable.

They become:

- Emotional anchors

- Psychological reassurance

- Cultural storytelling tools

Rather than predicting the future, these dreams help people face it with greater calm and confidence.

Final Thoughts: More Than Just Superstition

The tradition of good dreams before exams in Korea is not about magical thinking—it is about hope, reassurance, and emotional resilience.

In moments where outcomes feel uncontrollable, dreams provide meaning. They give students permission to believe in themselves, even briefly. And sometimes, that belief is exactly what they need.

Whether you see dreams as symbolic messages, subconscious processing, or cultural rituals, one thing is clear: in Korea, a good dream before an exam is not just luck—it is comfort.